Introduction

Artificial intelligence has already reshaped productivity, delegation, and knowledge work. But in this surge of adoption, a deeper question has begun to surface: what exactly are we outsourcing when we outsource thinking itself? In his recent Harvard Business Review article, “What’s Lost When We Work with AI, According to Neuroscience”, David Rock offers a rare neuroscientific critique of cognitive offloading. His central warning is not about job loss or automation, but something more fundamental: the erosion of metacognition, the very processes that let humans make meaning, form insight, and build shared understanding.

Rock illustrates this through a striking anecdote. At Davos, many executives did not attend meetings personally. Instead, they sent AI agents to join discussions, take notes, and mail back summaries. As he describes, “we ended up with six humans and six AI agents”. The result was a room drained of depth: “conversations increasingly felt flat and empty, devoid of the rich discussion I was expecting.” That emptiness, he argues, is not incidental. It is the predictable neural cost of removing ourselves from the situations where thought is formed.

In this briefing, we analyze the core neuroscientific claims of the article, explain why AI-generated summaries are not cognitive equivalents to participation, and explore how organizations can use AI strategically without degrading the “stuff of thought”.

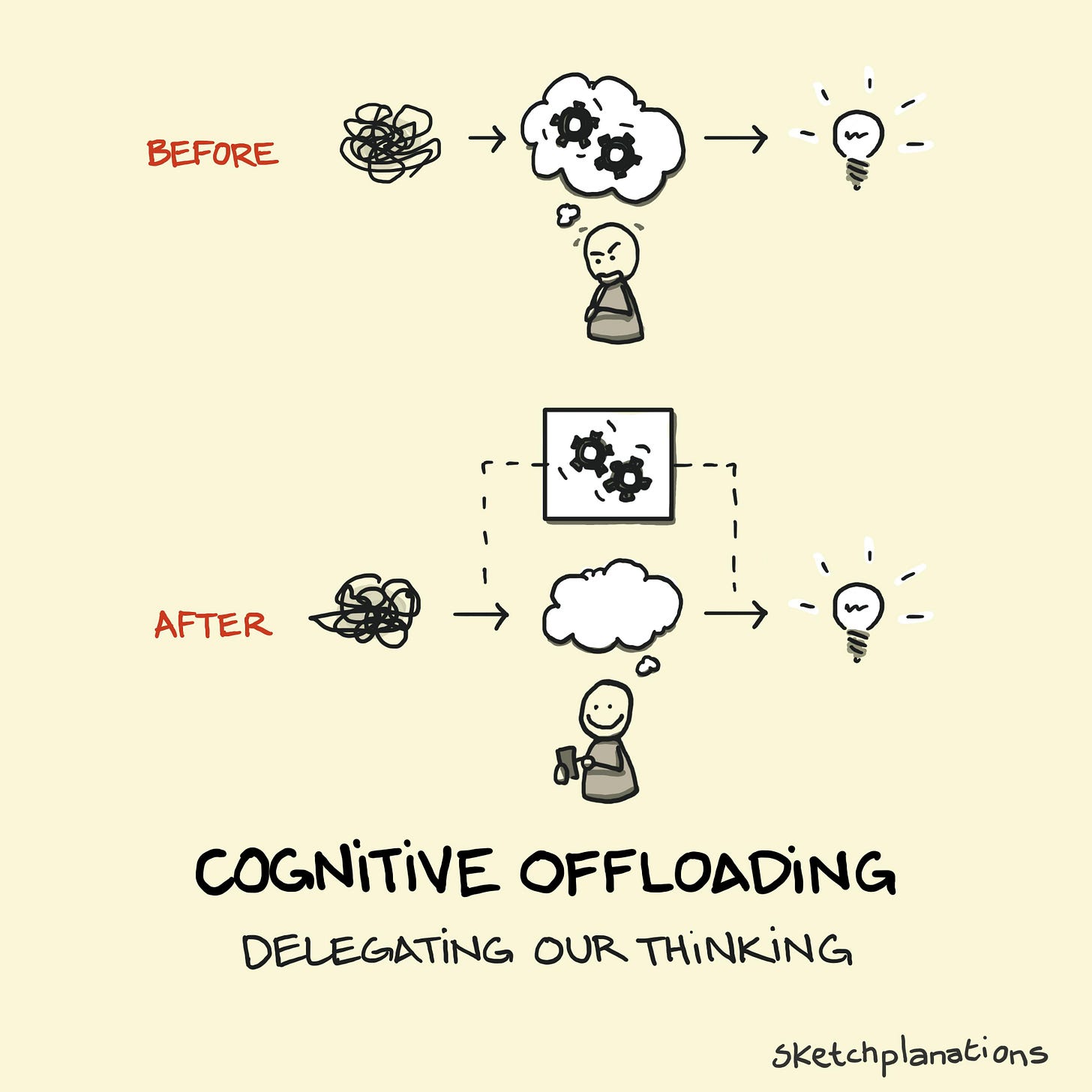

1. The Hidden Cost of Cognitive Offloading

Rock notes that AI tools promise efficiency, accuracy, and lower cognitive load. Yet he asks a deeper question: “What non-obvious benefits of human cognition are we surrendering in the process?”

This concern centers on cognitive offloading, the outsourcing of mental processes to external systems. Offloading is not new. Writing, calculators, and search engines all qualify. But generative AI differs because it replaces not only memory or computation, but the process of thinking itself.

Rock illustrates this with a simple but powerful example: reading an AI meeting summary. It may feel sufficient, but according to neuroscience it bypasses mechanisms crucial for:

-

Encoding information

-

Deep comprehension

-

Shared understanding

-

Insight formation

As Rock states, “We might grasp the plot, but we miss the richness, depth, and characters that make it memorable.” The analogy to cliff notes is deliberate. Summaries can reproduce content, but they cannot reproduce cognition.

2. Attention, Presence, and the Social Brain

One of the strongest claims in the HBR article is that attention is a social phenomenon. Rock writes: “Being in the presence of others, even in virtual settings, increases the strength of our attention on ideas and the neural circuits that support them.”

The neuroscience is clear. Humans evolved to monitor social cues constantly. This tuning of the social brain amplifies our attention networks whenever other minds are present. In practice, it means:

-

Our brain encodes information more deeply when others are watching.

-

We process ideas more robustly during live interaction.

-

We learn better when we must explain, defend, refine, or negotiate ideas socially.

Rock highlights neural synchrony, a measurable alignment of brain activity across participants. Research shows that synchrony predicts better shared understanding, more cohesive teams, and faster problem solving.

AI summaries cannot reproduce this because they compress the conversation into information without the conditions that produced the understanding. As Rock puts it: “We’re not moved by the book summary, and we’re not moved by the summary of the meeting either.”

This is not a matter of preference. It is a matter of neurobiology.

3. Spreading Activation: Why Thinking With Others Makes Us Smarter

A second key mechanism that disappears in AI-mediated work is spreading activation. Rock explains:

“When you think about an idea, this thought process activates a certain number and pattern of circuits. When you then speak about that same idea to another person, you activate a different set of circuits.”

This dual activation triggers:

-

More associations

-

More implications

-

More pattern recognition

-

More conceptual integration

This is how deep thinking happens: ideas collide with other ideas in real time, across multiple neural systems. AI, by giving us direct outputs without dialogue or negotiation, short-circuits this process. Rock warns that our thoughts become “surface-level and one-dimensional” when the brain is not given space to elaborate.

He cites recent evidence: “83 percent of individuals who used gen AI to help them write an essay struggled to remember the content of their work.” Offloading removes the cognitive labour that produces durable memory.

When AI does the thinking, we see the solution, but we do not undergo the process required to own it.

4. The Neuroscience of Insight and Motivation

Perhaps the article’s most important insight is this: AI may steal our insights from us.

Rock writes, “Every invention and breakthrough begins with an insight.” Insight is not just a cognitive event. It is tied to:

-

Dopamine release

-

Motivation

-

Agency

-

Long-term memory

When AI produces ideas on our behalf, we circumvent the neural pathway that produces the “aha” moment. As Rock warns, “We may quickly have access to the solutions, but we lose the motivating power that results from reaching a solution ourselves.”

This is not simply a philosophical concern. Organizations depend on human insight. Strategy, creativity, leadership, and innovation all require the internal motivational energy that only self-generated insights create. AI can accelerate execution, but cannot replicate that motivational spark.

5. The Real Question: What Should We Keep and What Should We Hand Over?

Rock concludes with a sober warning: “We may need to pause to reflect on what we’re outsourcing not just in terms of tasks, but in terms of thinking itself.”

The conclusion is not anti-AI. It is anti-unreflective adoption. The challenge is deciding what parts of cognition we can hand off without degrading:

-

Attention

-

Memory

-

Insight

-

Collaboration

-

Identity

His final provocation stands as the guiding question for every leader:

“How should we use AI to enhance, not replace, our best thinking?”

This will require guardrails not only for accuracy and safety, but for cognitive integrity. The future of work will not be defined by how much AI we use, but by how carefully we decide when to use it.

Conclusion: Preserving the Stuff of Thought

The Harvard Business Review article is ultimately a warning about the erosion of the very capacities that make human work meaningful. Rock’s neuroscience-based argument shows that thinking with others is not an inefficiency to automate away. It is a biological mechanism for producing depth, memory, and innovation.

AI will remain indispensable. The productivity gap between adopters and non-adopters is widening quickly. But cognitive offloading cannot become cognitive replacement. What organizations must protect is not time or output, but the neurobiological conditions that make thinking possible.

AI will change how we work. The question is whether it will also change how we think. According to neuroscience, that depends entirely on the choices we make now.

For the full details: What’s Lost When We Work with AI, According to Neuroscience